Nomadic ecology shaped the highland geography of Asia's Silk Roads

Michael D. Frachetti, C. Evan Smith, Cynthia M. Traub & Tim Williams

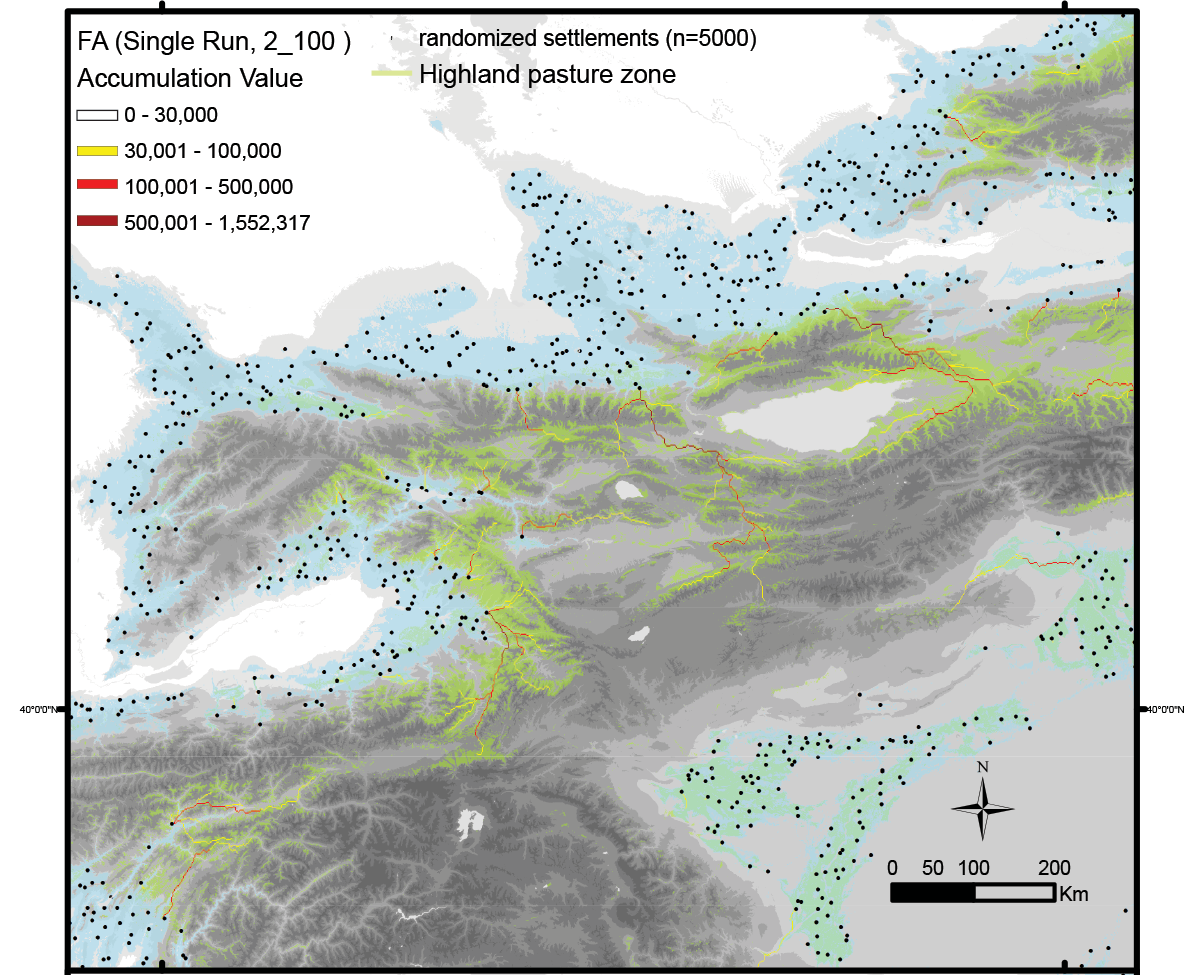

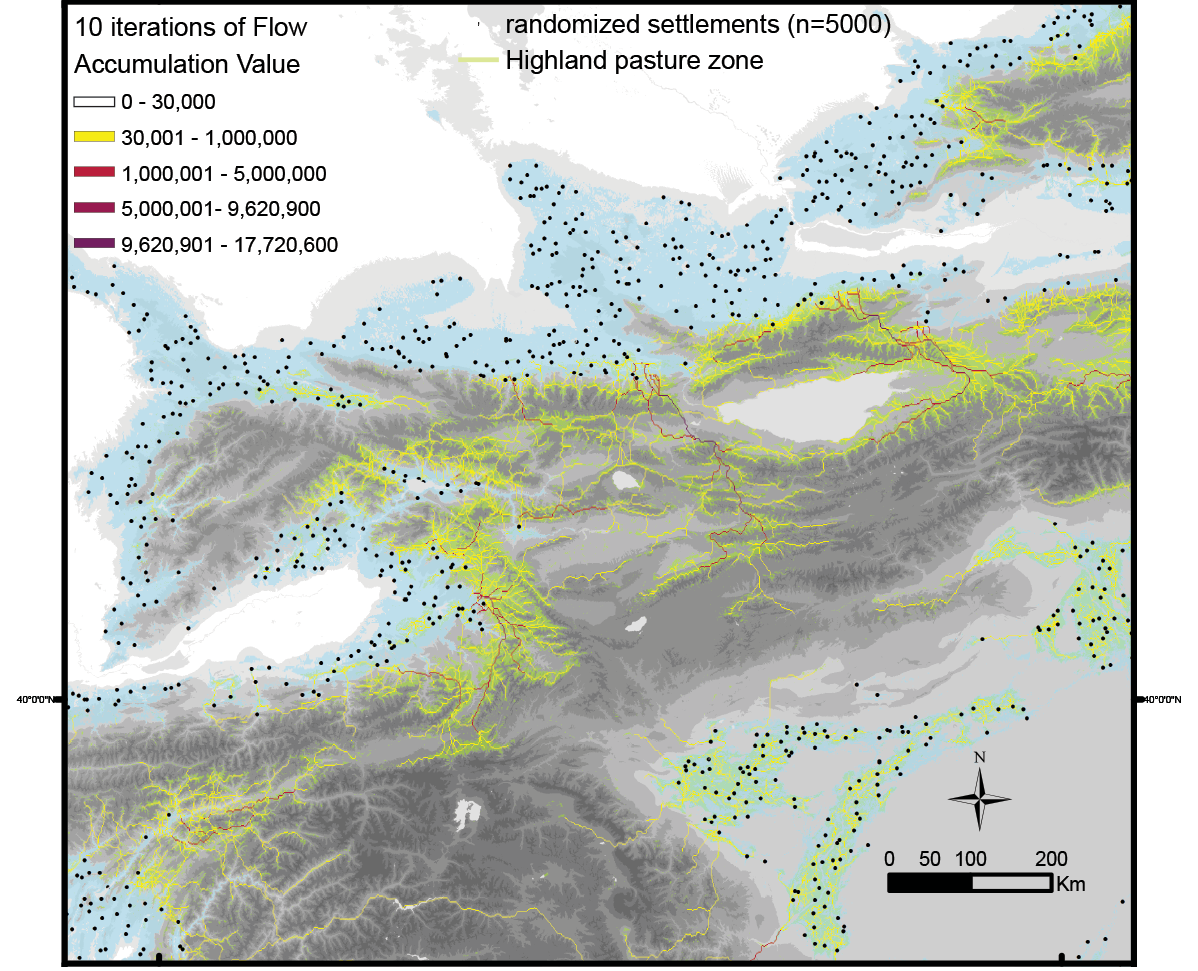

There are many unanswered questions about the evolution of the ancient ‘Silk Roads’ across Asia. This is especially the casein its mountainous stretches, where harsh terrain is seen as an impediment to travel. Considering the ecology and mobility of Inner Asian mountain pastoralists, we use “flow accumulation” to calculate the annual routes of nomadic societies (from 750 m to 4000m elevation).

Our methods

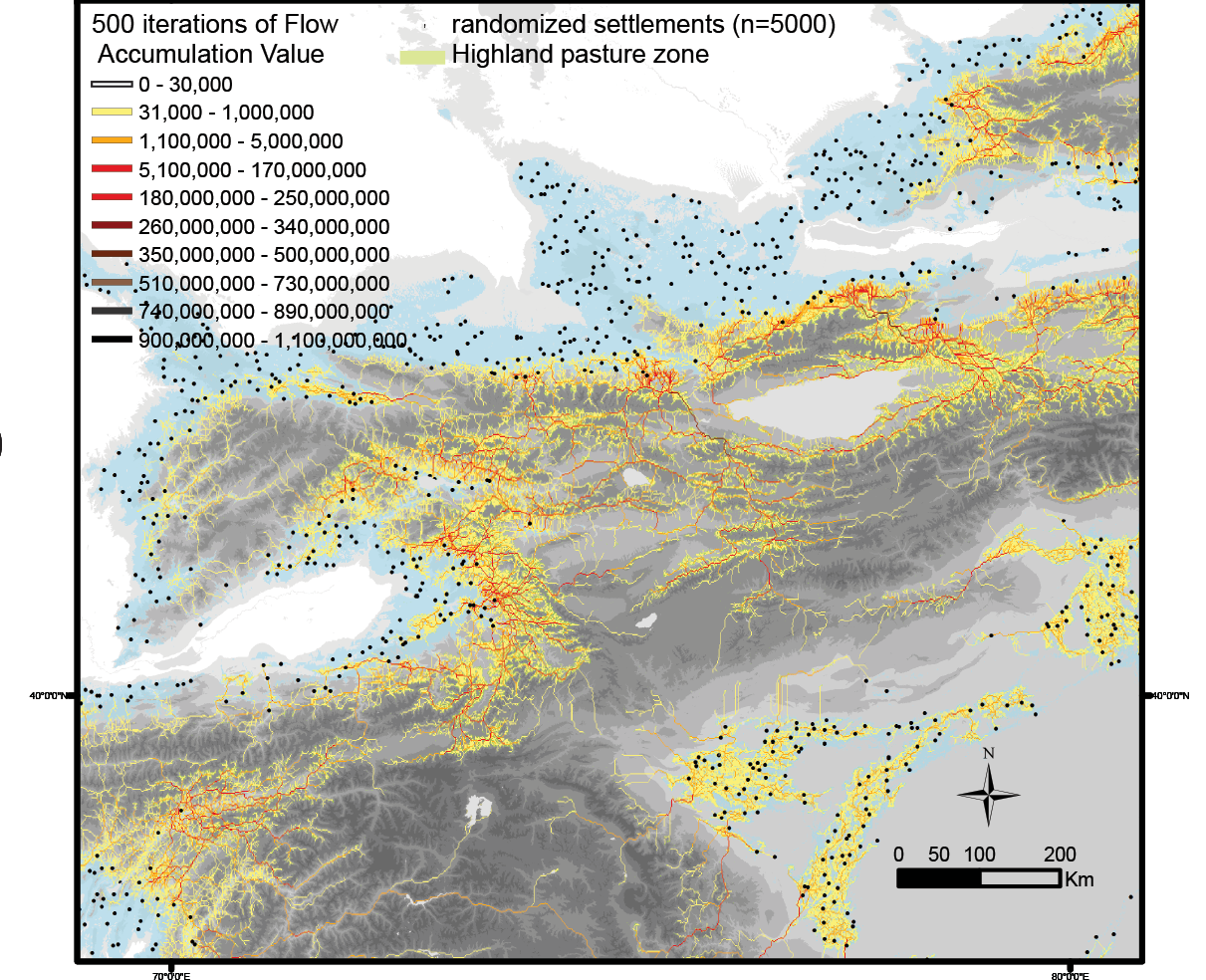

Aggregating 500 iterations of the model reveals a high-resolution flow network that simulates how centuries of seasonal nomadic herding could shape discrete routes of connectivity across the mountains of Asia. We then compare locations of known high-elevation Silk Road sites with the geography of these optimized herding flows, which shows a significant correspondence in mountainous regions.

Results Discussion

An extensive network of connectivity emerges as an aggregate effect of seasonal mobility amongst small and geographically sparse mobile herding populations across the highlands of inner Asia.

From our high-resolution aggregate flow accumulation maps, we conclude that the mountainous routes of the Silk Road more likely developed as a series of short-distance exchanges along herding routes, with travellers rarely covering long distances.

Our model also highlights potential pathways and connectivity in areas where historical Silk Road sites are less known archaeologically, such as west of Narat in Xinjiang China, which provides scholars the opportunity to target new regions for Silk Road research and exploration and to revise the history and cartography of interregional interaction on the basis of easily modelled variables.

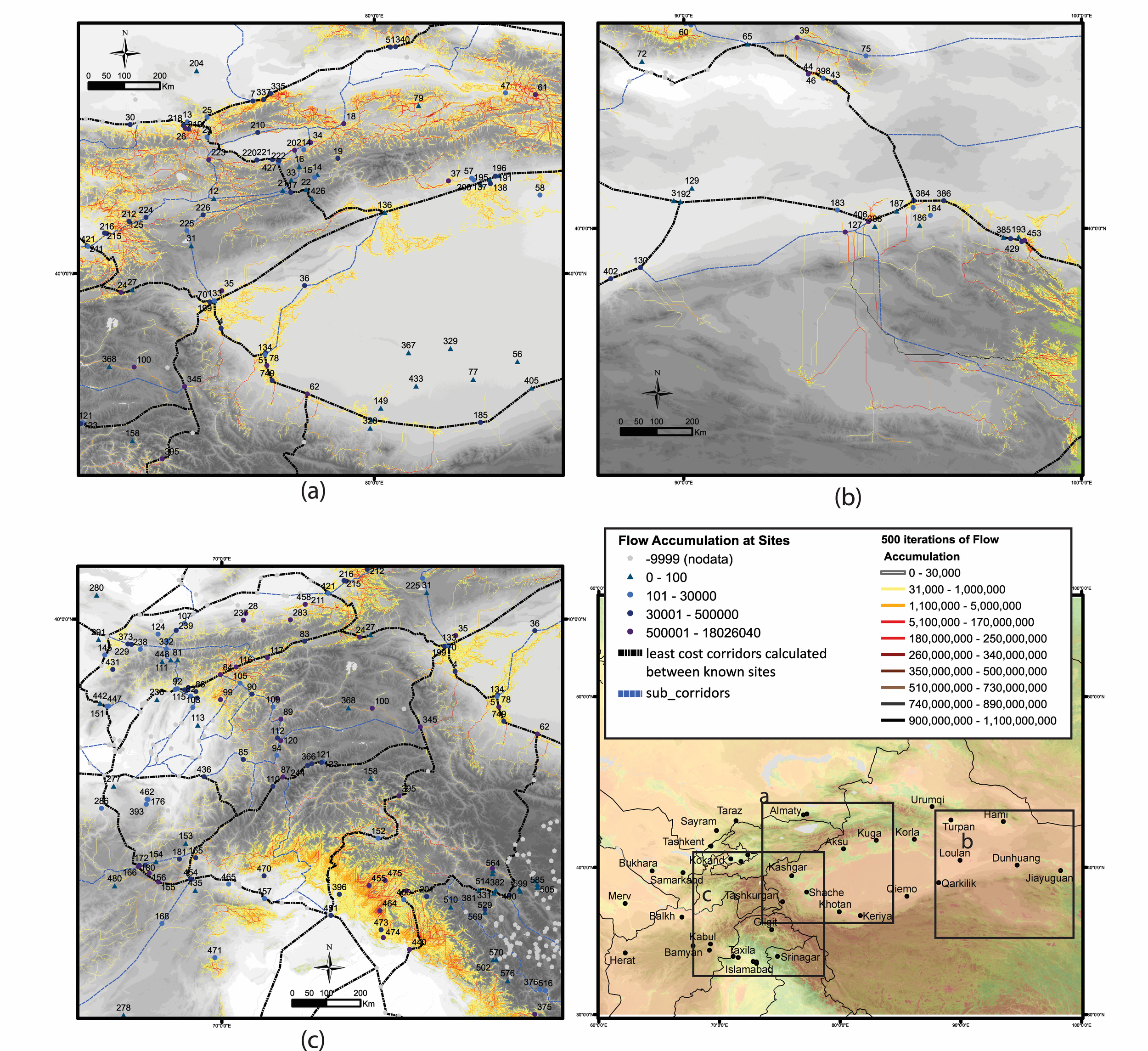

Comparative geography of proposed Silk Road corridors

Figure is calculated using least-cost (ease-of-travel) algorithms (black and blue lines) to connect known archaeological/historical sites and the simulated herding flow pathways from 500 aggregate runs of the PastPart model (yellow and red ‘flow’ network).

The pastoralist participation model is intentionally agnostic to the many social factors that unquestionably shaped the dynamic interactive history of prehistoric and historical societies along the Silk Road. Although our model does not fully provide explanations for the economic, institutional, and cultural expressions that define the Silk Road archaeologically or historically, it does allow us to illustrate the important influence that small-scale mobility patterns can have in shaping macro-scale networks.

At its most fundamental, the pastoralist participation model illustrates the potential ease by which highland herders probably found themselves—through their most basic of economic strategies—paving the way for the enduring pathways of Silk Road participation across highland Asia. The spatial correlation between long-standing ecologically derived herding flows and the historically diverse range of known highland Silk Road sites (for example, towns, caravanserais, mausoleums, religious centres) indicates that highland nomadic mobility intersected with institutional trends that resonated far beyond the mountainous region of Asia.